VIRGIL 4 Jan 2020

If Virgil told you about an article arguing that the current system can’t handle the challenges of globalization—pointing to “the completely unprecedented personal economic insecurity of working people, from industrial workers and white-collar clerks to medium-high managers”—you might be inclined to react as follows: “That’s old news. I’ve read a hundred articles making that point, again and again, over the last few years—quite a few of them, in fact, at Breitbart News.”

Okay, but what if Virgil told you that this particular article was written in…1994? As in, a full quarter-century ago? In other words, way ahead of its time?

It’s worth recalling that back in 1994, in the wake of the end of the Cold War, the elites were in love with globalization; they were avidly consuming utopian books such as The Borderless World, The End of History, and The Twilight of Sovereignty.

And yes, 1994 was the year that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect. As President Bill Clinton said as he signed the trade treaty, “NAFTA means jobs. American jobs, and good-paying American jobs.” In fact, Clinton mentioned the word “jobs” a full 50times in that speech. Indeed, all that repetition might make one think that the 42nd president was trying really hard to convince Americans that he was telling the truth about their jobs.

Interestingly, as Clinton spoke in support of the trade deal, he was joined at the podium by former presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush; in other words, at the elite level, support for NAFTA was virtually unanimous. Everything would be wonderful, we were assured, if the globalists got their way.

Yet back then, one observer was having none of this giddy optimism. In April 1994, veteran D.C. think-tanker Edward Luttwak, writing in the London Review of Books, argued that trade deals such as NAFTA were hollowing out Middle America—and that the elite didn’t either notice or care: “Neither the moderate Right nor the moderate Left even recognizes, let alone offers any solution for, the central problem of our days: the completely unprecedented personal economic insecurity of working people, from industrial workers and white-collar clerks to medium-high managers.”

Luttwak’s point was that globalization and trade were a threat to the cultural and economic structures of each and every developed country. That is, long-standing and intricate systems of work and life were now being exposed to the “tidal waves of change in the global economic ocean.”

Defenders of such planetary tidal-waving said that it was inevitable, given that countries such as Mexico and China were entering the world economy—and that as they did so, of course they would be making big waves. And yet Luttwak’s point was that the elites were neither noticing nor caring about the societal impact of these waves crashing on the home country.

Luttwak was especially cutting in his dismissal of the Republican response: “In this situation, what does the moderate Right … have to offer? Only more free trade and globalization, more deregulation and structural change, thus more dislocation of lives and social relations.”

Luttwak added that Republicans were in the curious position of being economic libertarians and, at the same time, social conservatives. That is, they were more than a little schizophrenic, because wide-open economics typically pulverizes any particular cultural heritage. As he put it, the standard Republican “after-dinner speech is a two-part affair, in which part one celebrates the virtues of unimpeded competition and dynamic structural change, while part two mourns the decline of the family and community ‘values’ that were eroded precisely by the forces commended in part one.”

Okay, so Luttwak gets credit for being ahead of his time—way ahead. He had grasped the reality that economic growth and transformation is dislocating, especially when that economic growth is differentialized within the society, as owners prosper and workers suffer.

As Luttwak put it, the voguish business-consultant jargon of the era—concepts such as “restructuring” and “re-engineering”—was mostly just code words for downsizing and outsourcing. That is, a given company might “grow” by slicing domestic employment and moving production overseas, but it was growing only its own profits, not its contribution to American society.

Yes, Luttwak’s was a lonely voice in 1994. And yet he knew that he was on to something; in 1998 he published the equally prescient Turbo-Capitalism: Winners and Losers in the Global Economy. Describing the contemporary system, he noted, “It enriches industrializing poor countries, impoverishes the semi-affluent majority in rich countries, and greatly adds to the incomes of the top 1 percent on both sides who are managing the arbitrage.”

As we all know, it took a couple of decades for people to see that Luttwak’s critique was dead-on. Back in the ’90s and ’00s, the elite consensus held that if planetary arbitrageurs—operating in financial and informational hubs such as New York City and San Francisco—were prospering, that was a good enough sign that everyone was prospering. In this reckoning, what’s good for Goldman Sachs and Google is good for America. And of course, if more immigrants—legal or otherwise—were needed to serve in the service economy, well, that was good, too.

We can add that this smug view was bipartisan: President George W. Bush shared Bill Clinton’s economic opinions; indeed, if anything, Bush was even more of an enthusiast for closer integration with Mexico. (Although, of course, Bush ended devoting most of his presidency to the folly of closer integration with Iraq and Afghanistan.) And as for Barack Obama, he was another globalist—seeking closer integration with many countries, including China.

Thus it took until the 2016 election for a presidential candidate to say, “Enough!” That candidate, of course, was Donald Trump. (And in an odd way, some of Trump’s anti-globalization arguments were echoed by another prominent ’16 candidate, Sen. Bernie Sanders.)

President Donald Trump speaks to auto workers at the American Center for Mobility March 15, 2017, in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Trump discussed his priorities of improving conditions to bolster the manufacturing industry and reduce the outsourcing of American jobs. (Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

In the memorable words of Stephen K. Bannon, head honcho at the Trump presidential campaign and then for a time the top strategist in the Trump White House, “The globalists gutted the American working class and created a middle class in Asia.”

By now, most national politicians, in both parties, pay at least lip service to the Luttwak-Bannon argument; there’s a realization that the American middle class paid the price while the bi-coastal elite reaped the reward. And that’s why the various trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific trade deals favored by the Obama administration, and Hillary Clinton, seem to be dead.

And as an aside on the 2020 presidential campaign, post-Clinton Democrats, having finally soured on Bill-and-Hill-style neoliberalism, are now targeting White House hopeful Pete Buttigieg for his association with McKinsey & Co. That’s the notorious and scandal-plagued “management consulting” firm that’s been at the forefront of so many corporate decisions to lay off and to outsource, among other forms of international skullduggery. Buttigieg is easily recognized as the candidate most likely to revive those globalist trade deals, in keeping with his overall Harvard mentality; no wonder he’s so popular with the Sonoma crystal wine-cave fundraisers.

Okay, so Luttwak stands as a prophet. However, let’s hope that he isn’t proven to be right about everything that he wrote back in 1994. After all, the headline atop Luttwak’s piece, a quarter-century ago was scary. It bannered, “Why Fascism is the Wave of the Future.” That’s right, the “F” word, Fascism.

Luttwak was careful to point out that Fascism started out separate and distinct from Nazism. That is, the Fascist movement of Benito Mussolini, who took power in Italy in 1922, may have been un-democratic and illiberal, but it was not Hitlerian in its war-mongering, antisemitic, and genocidal evil. In fact, within the early Italian Fascist movement, Jews were well represented. But then, of course, Mussolini took on a catastrophic turn in the 1930s, after Hitler came to power in Germany, and Italy signed on to Hitler’s Axis.

September 1937: Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, the leader of Nazi Germany, in Munich. (Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Mussolini was later fully and criminally complicit in Hitler’s wickedness, and yet still, Luttwak is right to draw a distinction between early Fascism and Nazism.

And so it’s with the early-Mussolini model in mind that Luttwak argued, back in ’94, that severe economic dislocation would open the door to unpleasant political reaction:

… and that is the space that remains wide open for a product-improved Fascist party, dedicated to the enhancement of the personal economic security of the broad masses of (mainly) white-collar working people. Such a party could even be as free of racism as Mussolini’s original was until the alliance with Hitler, because its real stock in trade would be corporativist restraints on corporate Darwinism, and delaying if not blocking barriers against globalization.

Luttwak himself is no Fascist, and yet as a learned historian and acute observer, he could see, a quarter-century ago, that global trends were pushing Americans toward the point where an anti-liberal backlash would come in full force.

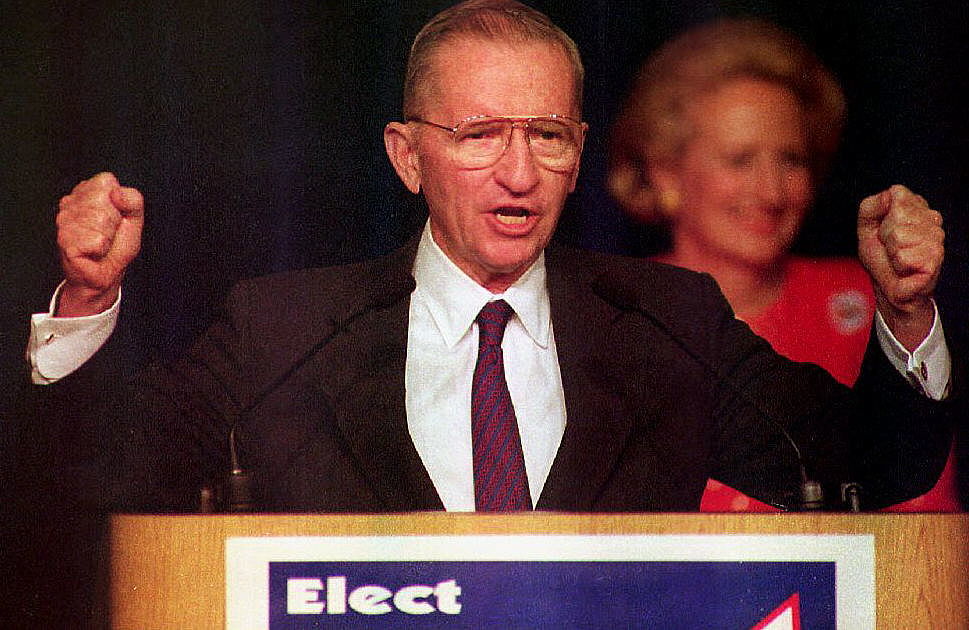

Interestingly, in that 1994 article, the American figure that Luttwak pointed to, as an early indicator, was Ross Perot, the businessman-turned-populist. Perot was no Fascist, but his success as a political outsider was, indeed, a stark repudiation of the liberal and bipartisan status quo. Just two years earlier, Perot had, of course, run for president as an independent, winning an impressive 19 percent of the national vote. And what was one of Perot’s signature issues? Why, it was his opposition to NAFTA. That trade deal, he said, would create a “giant sucking sound,” as American jobs went south of the border.

U.S. independent presidential candidate Ross Perot delivers his concession speech to the crowd gathered November 3, 1992, at his election night headquarters. (PAUL RICHARDS/AFP via Getty Images)

Perot was mocked at the time, and yet, of course, he has been proven right, and Clinton—plus fellow NAFTA cheerleaders Bush 41 and Bush 43—have been proven wrong. Just as Luttwak said it would, NAFTA turbo-charged North America, enriching the fat cats of Wall Street and Silicon Valley, while sending regular jobs from Ohio to Mexico.

But okay, just one last thing: What about that “F” word, “Fascism”? If Luttwak was correct in his economic and social predictions, might he be correct, too, in his political prediction, about the coming of a “product-improved Fascist party”?

Today, many on the left have their answer: Donald Trump is a Fascist. A Google search of “Donald Trump” and “Fascist” elicits millions of hits, including an October 2016 Washington Post op-ed entitled, “How fascist is Donald Trump?” And just on December 21, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, speaking to an audience in California, declared, “It is fascism, what we’re evolving into.”

Of course, the left was playing the “Fascist” smear game long before Trump. Both Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan were routinely labeled as Fascists, as was George W. Bush. And in 2004, the leading liberal group Moveon.org went there, equating Bush to, yes, Hitler.

Indeed, as the liberal Atlantic magazine acknowledged in 2016, it’s been a standard tactic of the left to smear just about every Republican as a “Fascist.” So as we can see, the left’s demagoguery has cheapened the word “Fascist” to the point of irrelevance; today, the “F” word is simply just one more insult in the left-wing arsenal.

So no, Trump is not a Fascist, and neither are Republicans. In fact, come to think of it, if we wanted to envision Fascism in the 21st century—allowing for changes in style and fashion—we might think of Antifa, which is the hipster name for Anti-Fascist.

As Breitbart News has pointed out, Antifa ideologists believe that violent thuggery on the streets is a key part of their strategy for provoking civil strife—and that, of course, is classic Fascism. So in other words, when we see the word “Antifa,” we should just delete the “Anti” and know that we’re seeing “Fa.”

An unidentified Rose City Antifa member flicks off to the police during a demonstration between the left and right at Pioneer Courthouse Square on June 29, 2019 in Portland, Oregon. (Moriah Ratner/Getty Images)

Andy Ngo, a Portland-based journalist, is seen covered in unknown substance after unidentified Rose City Antifa members attacked him on June 29, 2019 in Portland, Oregon. (Moriah Ratner/Getty Images)

An Antifa demonstrator has a heated exchange with a pro-Trump supporter during the Denver March Against Sharia Law in Denver, Colorado on June 10, 2017. (JASON CONNOLLY/AFP via Getty Images)

Of course, there’s more going wrong with American society than just Antifa hooliganism. The sort of churn that Luttwak lamented a quarter-century ago has been profoundly damaging to the social fabric, and we see it in the worsening of societal indicators, including flattened wages, family breakdown, opioid use, and gun violence, including mass shootings.

And yes, it’s possible that if the deterioration continues, some sort of strong antidote—more precisely, a horrible “antidote”—could emerge.

So if we want to make sure we can fend off even the threat of Fascism, we should start with leadership that’s both strong and wise. Strong leaders stand up to extremist Antifa-type violence, of course, and yet, at the same time, they are wise enough to solve the underlying social conditions that contribute to extremism.

After all, Italian Fascism emerged from the wreckage of World War One. And we can add that Communism—another terrible extremism that’s a kind of mirror to Fascism—emerged in Russia at around the same time, in the wake of the same war. And a decade later, Nazism emerged from the war, too, as well as from the Depression.

So obviously we start our anti-Fascism plan with a commitment to overall peace and prosperity. That is, no stupid foreign wars, no crazy economic policies. And then we have to get to work on the healing of our homeland, repairing the many social and cultural injuries and injustices caused by turbo-capitalism.

EconomyPoliticsAntifabenito mussoliniBill ClintonDonald TrumpEdward N. LuttwakfascismfascistsGeorge BushglobalismHitlerNAFTAPete ButtigiegRoss Perot

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.