Pieces of territory belong to institutions, not to racial groups.

The United States, like all nations, was created through territorial conquest. Most of its current territory was occupied or frequented by human beings before the U.S. came; the U.S. used force to either displace, subjugate, or kill all of those people. To the extent that land “ownership” existed under the previous inhabitants, the land of the U.S. is stolen land.

This was also true before the U.S. arrived. The forcible theft of the land upon which the U.S. now exists was not the first such theft; the people who lived there before conquered, displaced, or killed someone else in order to take the land. The land has been stolen and re-stolen again and again. If you somehow destroyed the United States, expelled its current inhabitants, and gave ownership of the land to the last recorded tribe that had occupied it before, you would not be returning it to its original occupants; you would simply be handing it to the next-most-recent conquerors.

If you go back far enough in time, of course, at some point this is no longer true. Humanity didn’t always exist; therefore for every piece of land, there was a first human to lay eyes on it, and a first human to say “This land is mine.” But by what right did this first human claim exclusive ownership of this land? Why does being the first person to see a natural object make you the rightful owner of that object? And why does being the first human to set foot on a piece of land give your blood descendants the right to dispose of that land as they see fit in perpetuity, and to exclude any and all others from that land? What about all the peoples of the world who were never lucky enough to be the first to lay eyes on any plot of dirt? Are they simply to be dispossessed forever?

I have never seen a satisfactory answer to these questions. Nor have I seen a satisfactory explanation of why ownership of land should be allocated collectively, in terms of racial or ethnic groups. In general, the first people who arrived on a piece of land did so in dribs and drabs, in small family units and tiny micro-tribes that met and married and fought and mixed and formed into larger identities and ethnicities and tribes over long periods of time. In most cases, the ethnic groups who now claim pieces of land as their own did not even exist when the first humans discovered or settled that land.

But even in those cases when it did exist, why should land ownership be assigned to a race at all? Why should my notional blood relation to the discoverers or the conquerors of a piece of land determine whether I can truly belong on that land? Why should a section of the map be the land of the Franks, or the Russkiy, or the Cherokee, or the Han, or the Ramaytush Ohlone, or the Britons? Of course you can assign land ownership this way — it’s called an “ethnostate”. But if you do this, it means that the descendants of immigrants can never truly be full and equal citizens of the land they were born in. If Britain is defined as the land of the Britons, then a Han person whose great-great-great-grandparents moved there from China will exist as a contingent citizen — a perpetual foreigner whose continued life in the land of their birth exists only upon the sufferance of a different race. This is the price of ethnonationalism.

The downsides of ethnonationalism have been exhaustively laid out in the decades since World War 2, and I’m not going to reiterate them all now. Suffice it to say that most nations of the world have moved away from ethnonationalism — there is an informal sense in which some people still think of France as the land of the Franks and so on, but almost all nations define citizenship and belonging through institutions rather than race. Israel, one of the few exceptions to this rule, receives a large amount of international criticism for defining itself as an ethnostate.

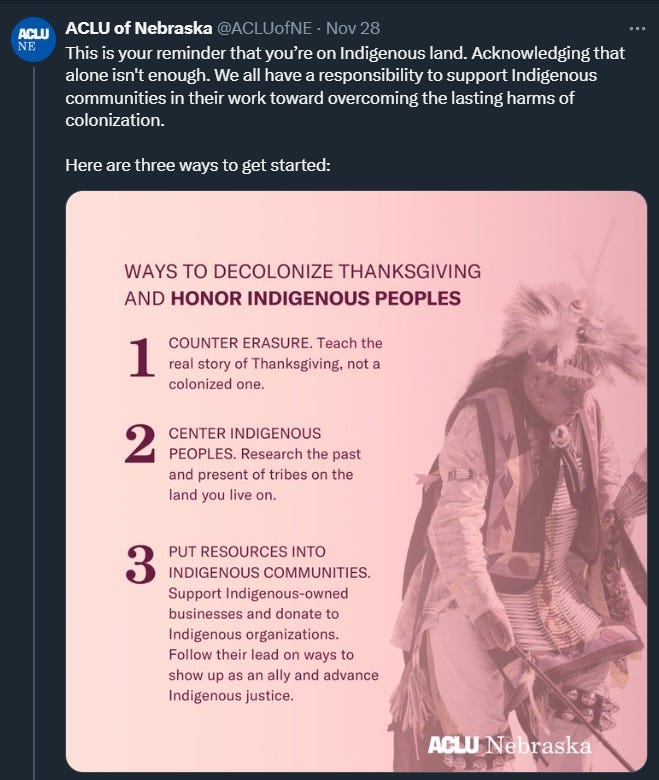

And yet these days I am subjected to a constant stream of ethnonationalist claims from progressives in the country of my birth. Here’s one from the ACLU of Nebraska:

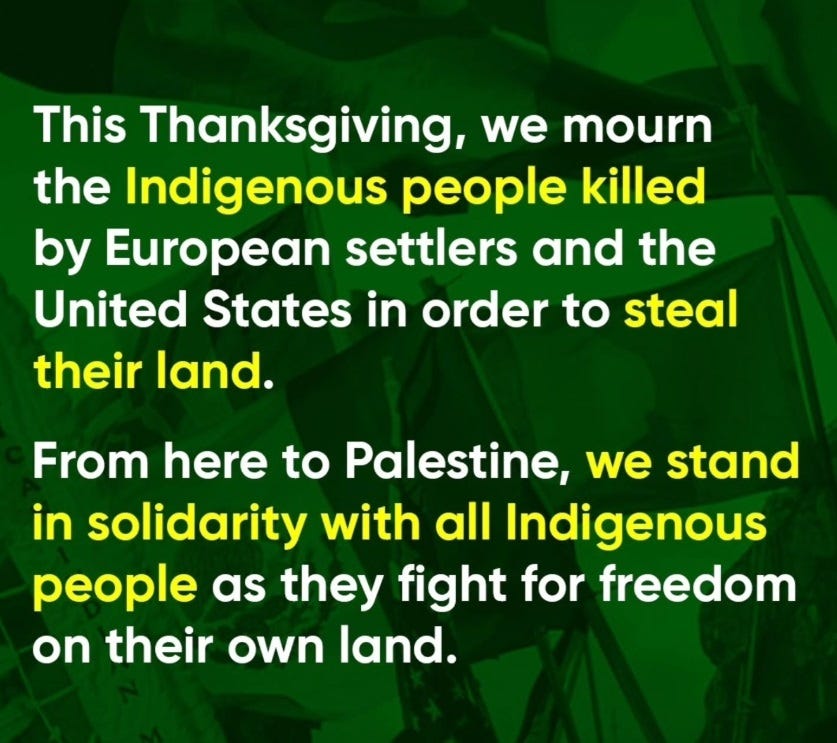

And here’s an Instagram post from Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib:

This isn’t just something you see on social media around Thanksgiving. “Land acknowledgements” have become ubiquitous in progressive spaces and institutions — just the other day I saw one at my friend’s community dance recital.

These land acknowledgements are, legally speaking, incorrect — there is no legal sense in which the land on which they are being performed belongs to a Native American tribe. These are moral claims about rightful land ownership. But the moral principle to which they appeal is ethnonationalism — it’s the idea that plots of land are the rightful property of ethnic groups.

There is an obvious moral appeal to these land acknowledgments. They are a way of decrying the brutal, cruel, violent history of conquest and colonization. And they probably feel like a way of standing up for the weak, the marginalized, and the dispossessed.

Yet what should we think of the morality of following the principles behind land acknowledgements to their logical conclusion? “Decolonization” of the land of the U.S. would likely be an act of ethnic cleansing surpassing even the previous conquests — there are 330 million people here now, and almost none of them descend from Native Americans. An attempt to dispossess 330 million people would inevitably involve violence on a colossal scale. Here was Najma Sharif Alawi’s famous tweet right after the October 7th Hamas attacks on Israel:

Of course, “colonizers” could presumably avoid violent death or second-class citizenhood by voluntarily deporting themselves. But where would they go? Take me, for example. My ancestors were Lithuanian Jews. I could leave the country of my birth and go “back” to Lithuania — a land I don’t know, whose language I don’t speak. Yet my ancestors were not “indigenous” to Lithuania either; they moved there from somewhere else. What if the ethnic Lithuanians chose not to accept me? Where would I go then? Israel? But the folks who do land acknowledgements would consider me a “colonizer” there as well.1

Would I then wander the Earth, desperately seeking some ethnostate that would allow me and my descendants to live there as a permanently precarious resident aliens?

Once the logic of land acknowledgements and “decolonization” is followed, it leads very quickly to some very dark futures. Assigning each person a homeland based on their ethnic ancestry, and then declaring that that homeland is the only place they or their descendants can ever truly belong, would not be an act of justice; it would be a global nightmare made real, surpassing even the horrors of previous centuries.

And in practice, any attempt to create such a world would inevitably lead to violent resistance by the groups in danger of being “decolonized”. The orderly world of nation-states would dissolve into a chaotic free-for-all of competing irredentist claims, backed by genocides and expulsions. Ten thousand October 7th-style attacks would be followed by ten thousand Gaza-style wars.

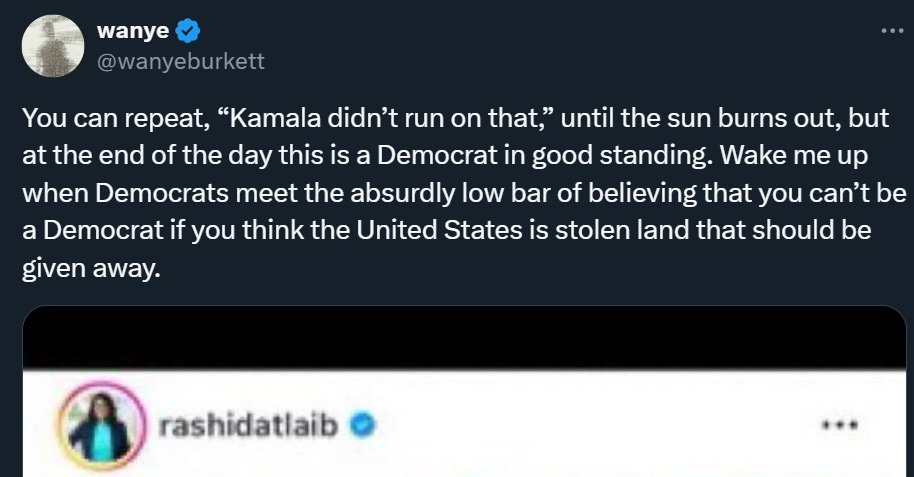

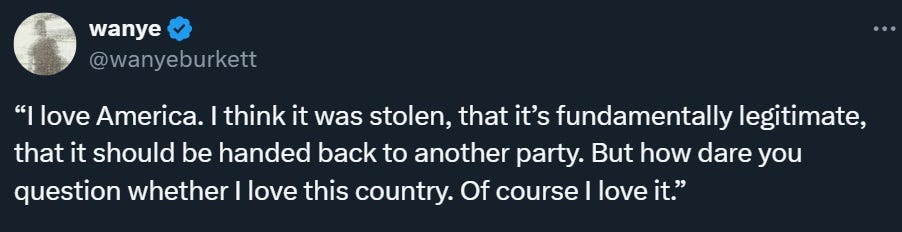

I do not want that, and you should not want it either. The American people certainly don’t want it, and the insistence of progressives on intoning land acknowledgements has probably tanked the movement’s cachet in wider society. I agree with Wayne Burkett when he says that land acknowledgements have probably hurt the Democratic party:

Americans do not want to see their country destroyed in the name of irredentist ethnonationalism. Nor do I blame them.

So does this mean we should paper over, ignore, or deliberately forget America’s history of violent conquest? Absolutely not. That history ought to be remembered, so that we don’t repeat it in the present day. The world’s evolution from one based on ethnic cleansing and territorial conquest to one based on fixed borders and institutions is something to celebrate — and something we must fight to preserve. We need to remember what the world used to be like, precisely so we can avoid backsliding. The most recent of conquests, expulsions, and genocides should be the last to ever happen.

And what of the Native Americans who still live in America today? Must they simply be regarded as the unlucky losers of history, and told to either assimilate into broader American society or shut up?

Absolutely not. For one thing, tribal organizations still exist — they may notionally represent ethnic groups, but they are institutions. And they are institutions with which the United States has many agreements and legal obligations that must be honored, which often give the tribes sovereignty over areas of land. Neil Gorsuch has been especially active in pushing the Supreme Court to uphold tribal rights, and I think this is a good thing.

But respect for Native American tribal organizations doesn’t have to stop at ancient obligations. There are ways to incorporate those tribes into the modern American nation that both respects them and their history and helps them prosper in the present.

Vancouver, Canada shows us an example of how this can be done. Part of Vancouver’s downtown urban area is officially under the governance of the Squamish Nation, rather than the city itself. The Squamish Nation, realizing they could do whatever they wanted with that land, decided to build a giant high-rise housing development:

Over the next few years, that skyline will get a very large new addition: Sen̓áḵw, an 11-tower development that will [put] 6,000 apartments onto just over 10 acres of land in the heart of the city. Once complete, this will be the densest neighbourhood in Canada, providing thousands of homes for Vancouverites who have long been squeezed between the country’s priciest real estate and some of its lowest vacancy rates.

Sen̓áḵw is big, ambitious and undeniably urban—and undeniably Indigenous. It’s being built on reserve land owned by the Squamish First Nation, and it’s spearheaded by the Squamish Nation itself, in partnership with the private real estate developer Westbank. Because the project is on First Nations land, not city land, it’s under Squamish authority, free of Vancouver’s zoning rules. And the Nation has chosen to build bigger, denser and taller than any development on city property would be allowed.

Here’s a picture of what it will look like:

An even bigger development called Jericho Lands is now being planned, by a consortium of tribal organizations, on land officially owned by Vancouver.

Hilariously, Vancouver’s NIMBYs are complaining, claiming that the developments are not in keeping with Indigenous tradition. But Canada’s First Nations seem to have little interest in hewing closely to other people’s view of what their traditions are. Modern people do not want to live like premodern farmers. They are not mystical Tolkien elves. They would like to have shiny new apartment buildings and walkable neighborhoods.

This, I believe, is the key to respecting and honoring Native Americans — not to focus on the tragedies of their past, but to give them the right to build a better future. Tribal lands should definitely have the autonomy to do whatever they want with their lands, including building housing or industry. In fact, we’re starting to see a pattern emerge where Native Americans embrace laissez-faire policies toward industry and manage to poach business from their over-regulated neighbors:

Tesla is ramping up efforts to open showrooms on tribal lands where it can sell directly to consumers, circumventing laws in states that bar vehicle manufacturers from also being retailers in favor of the dealership model…

Mohegan Sun, a casino and entertainment complex in Connecticut owned by the federally recognized Mohegan Tribe, announced this week that the California-based electric automaker will open a showroom with a sales and delivery center this fall on its sovereign property where the state’s law doesn’t apply…The news comes after another new Tesla showroom was announced in June, set to open in 2025 on lands of the Oneida Indian Nation in upstate New York.

This sort of thing could lead to a win-win for the U.S. and Native American tribes. American reindustrialization is being held back by a thicket of procedural requirements and local land-use regulations; if tribes were able to use their special legal status to circumvent those barriers, it could end up benefitting everyone.2 The tribes would get both jobs and the ability to tax local industry; America would get to execute an end run around the NIMBYs that are holding it back.

In fact, it’s probably possible for various American cities to turn over parts of their land to tribal jurisdiction, with the assistance of the federal government. This would probably result in dense urban developments like the ones being planned in Vancouver. But even if it didn’t, it could have other commercial benefits — again, a win-win for the U.S. and for the tribes. That would certainly be a lot more substantive than a bunch of land acknowledgements. And it would likely satisfy many people’s desire for “giving land back” to Native Americans, without embracing dubious moral principles of ethnic land rights and irredentism.

In other words, you’re not living on Indigenous land right now, but you could be in the future — and it might be pretty great.

The general principle here is that instead of a dark world of ethnic cleansing in the name of “decolonization”, we should try to build a bright future where Native Americans and the United States of America exist in harmony and cooperation rather than in conflict. And that principle doesn’t just apply to America, but to the whole world. The history of land ownership is a violent and terrible one, but that doesn’t mean the future has to be more of the same.

It is a bitter irony that many of the same people who morally condemn Israel for setting itself up as an ethnostate also justify its destruction using ethnonationalist principles. Personally, I tend to agree with the criticism of Israel’s ethnocentrism, but I don’t think replacing this with Palestinian ethnocentrism would make things better.

There’s a lot of historical precedent for this. For example, in the 1960s, Fairchild Semiconductor opened a factory on Navajo land in New Mexico, which was quite beneficial to the economy until an industry downturn and a labor dispute led to its demise in the late 70s.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.